Students from Ljubljana propose new street and traffic arrangements using data from traffic counting sensors

In Ljubljana, Slovenia, students from the Department of Urbanism at the University of Ljubljana tested the use of the data obtained from the Telraam devices, in the framework of the WeCount project. They were invited to participate in a guided analysis and contribute their understanding and interpretation of the data from traffic counting sensors.

As part of the Strategic Spatial Planning course at the Faculty of Architecture, an exercise was carried out in which the students became familiar with the WeCount project, ultimately taking up the role of local champions. In other words, the students became advocates for WeCount, its activities and its goals.

They presented the project to three random residents of the city of Ljubljana and asked them to join WeCount activities either as members or as users of the Telraam device. The exercise was organised to introduce the WeCount project, which focuses on public participation through citizen science activities in planning a better living environment, becoming acquainted with new technologies, registering traffic flows and obtaining user data in concrete cases.

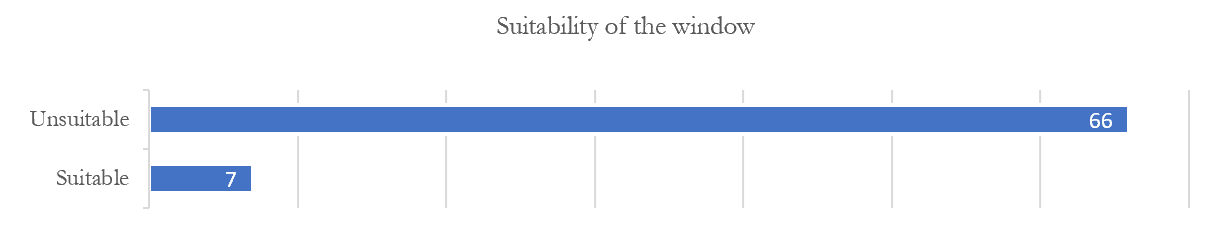

The students were introduced to the registration process and data collection in place. Most of the candidates - potential members or users - did not have a suitable window to assemble the traffic counting sensors. This is mainly due to the particular city layout of Ljubljana, which in the vast majority of cases does not offer satisfactory locations for the installation of a Telraam sensor.

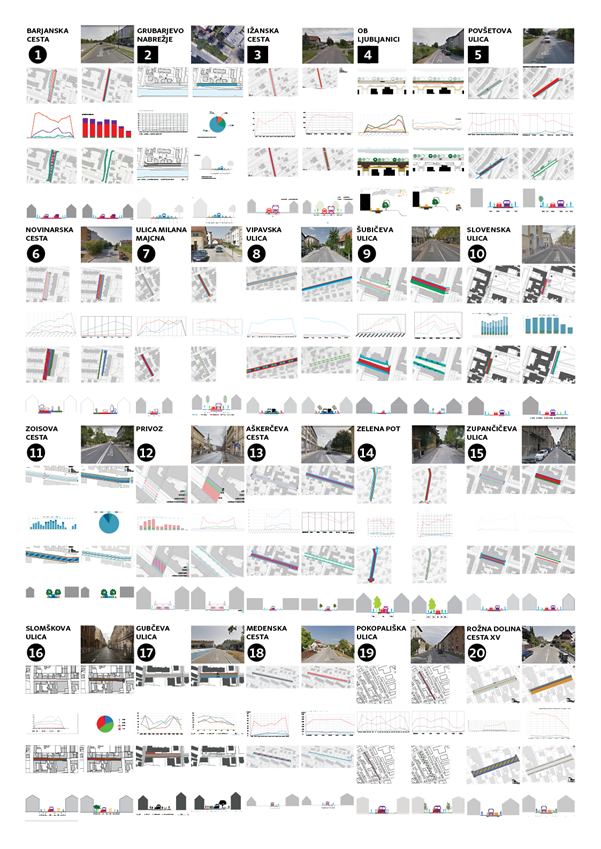

Alternatively, each student chose their own road section with an installed Telraam sensor and outlined the existing street location, including the traffic indicators of the selected street segment and the width of the road profile in relation to the road users – car drivers, pedestrians, cyclists. Included in this information summary was also a sketch of the location for which Telraam data was available.

Finally, the students compared the analysis of the selected street segment plan and section with collected Telraam data, which allowed them the opportunity to assess the traffic flows and the adequate road infrastructure. If these two did not match, they suggested improvements to the road profile and traffic arrangement.

The diagrams prepared by the students show the spatial proposals for the future streets and highlight the traffic density and structure. The density of bicycle traffic and the lack of cycle paths, high speeds in residential areas, the density of car flows in the city centre are just some of the problems identified. The students were enabled by data collected by the sensors to suggest quality solutions for redesigning the street profiles. The results of the exercises mostly revealed deviations from the existing traffic pattern and street profile. By applying the Telraam data, it was possible to design a better street profile based on actual rather than imaginary and speculative street use.

The example of the Grubar embankment clearly shows that the current street design is inadequate. Namely, Telraam data displays a high percentage of cycling traffic and therefore more attention should be paid to the inclusion of a bicycle lane. The proposed solution separates the bicycle lane from the road, which ensures greater safety for cyclists. A similar situation can be observed on Zelena Path and Pokopališka Street, where the students' new design also separates the bicycle lane from the car lane by narrowing the pavement or lane itself.

The data obtained from the Telraam sensors is essential as the proposed street design changes can be supported by solid evidence. The city of Ljubljana could have valuable tools at its disposal to improve the quality and quantity of cycling areas by making the streets cycling-friendly, which is usually reflected in the increase in the share of cycling trips in the city.

In this particular WeCount action, we focused on involving urban planning students as engaged citizens for two reasons: First, they are future planners who will work in city government, planning offices, etc., and they can broaden their horizons to be aware of citizen science approaches and their benefits already during their studies. At the same time, as not-yet-professionals, they can be an engaged and naturally interested and empowered group that can help find concrete solutions for bottom-up policy-making, and support the premise that active involvement of local citizens will be needed during the next period of urban redesign processes of the traffic system.