To progress, citizen science initiatives must share their best practices

Science has long drawn on the resources of everyday citizens. From crowd sourcing initiatives to small groups of local volunteers, discoveries and innovations in everything from weather patterns to maternity care have been underpinned by public data collection. As research is being pushed online, citizen science is an increasingly popular tool. However, if such initiatives are to be successful, they must learn from one another.

Research projects around Europe are turning to citizen science to secure valuable data. This is not an entirely novel phenomenon. The 2014 CERN Computing Challenge saw volunteers help CERN scientists simulate particle collisions in accelerators like the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), using their own technology; while QuakeCatcher Taiwan used sensors attached to participants’ computers to create a low-cost strong-motion seismic network. Ecologists, geographers and biologists alike are deploying the resources of citizens.

Mobile technology is making this process increasingly easier with apps such as iNaturalist and eBird enabling budding citizen scientists to report, track and share flora and fauna sightings. Such projects do not simply secure data, but engage and educate individuals, households, and communities in sustainability agendas, precipitating an intergenerational involvement with a spectrum of issues from air quality to pondlife.

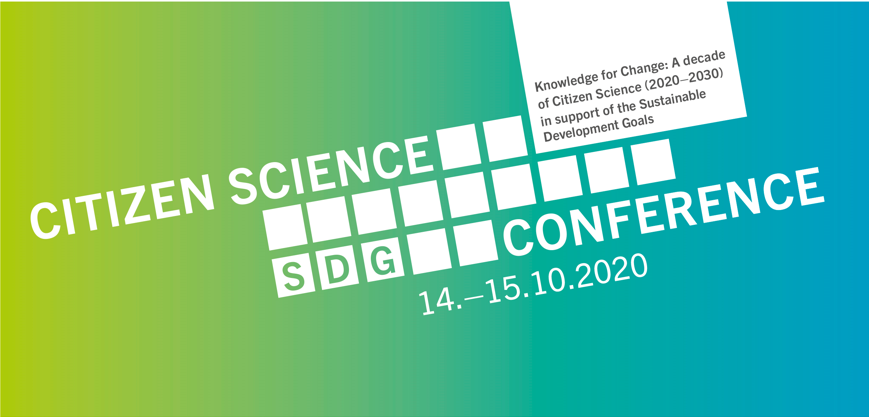

Mobility is also beginning to deploy citizen science. In 2018, ECF’s Hacking Copenhagen Demonstration utilised data collected from individual cyclists to understand cycling patterns, distinguish quality air, and identify the condition of local infrastructure. Each rider became a “sensor”, feeding into the project’s web of data on two wheeled movement across the city. Like WeCount’s own transit mapping, Hacking Copenhagen provided a comprehensive understanding of the transport eco-system and the geography of urban mobility.

As citizen science continues to develop and expand, knowledge sharing between such projects will be critical. Although these ventures tackle disparate topics, all confront corresponding practical concerns around the accessibility, functionality and scalability of data collection methods

This was an issue at point during the recent SDG Citizen Science conference. The event- which ran from 14-15 October- brought together policy makers, economists, and NGOs to discuss the progress being made in citizen science and how methodologies can be further utilised in achieving sustainable development goals.

As discussions at the conference exposed, citizen science projects have much to learn from the successes and missed opportunities of neighbouring programmes. When it comes to decisions regarding participant recruitment, communication channels and data collection technologies, best practice can – and should- be shared between citizen science projects in order to advance the entire sector.

Kris Vanherle from Transport & Mobility Leuven highlighted this when presenting WeCount’s pilot projects at the SDG conference. Reflecting on how WeCount mobilised local volunteers, Vanherle noted the importance of “local champions”, key individuals who build and maintain trust between participants, the scientific community and policy makers.

“They are a real asset for any citizen science activity,” he asserted,

Such advice is valuable for any project seeking to construct durable relationships between partners. Whether studying mobility, biodiversity, or public health, without direct and transparent linkages between each stakeholder, citizen science programmes risk fracturing before any useful data is even collated.

This is an issue which is likely to become increasingly critical as virtual data sharing platforms replace face-to-face networks as the pandemic continues to grip the globe.

“Moving online in a Covid-world is be a burden, but can also provide an opportunity, in some cases actually lowering threshold for people to participate,” warns Vanherle.

Without clear understanding of how to utilise available technology, participants will be unable to collect the necessary data- no matter how swanky the sensor! As a result, Vanherle’s presentation offered useful guidance for training volunteers, detailing the benefit of triangulating online training and recruitment with brief face to face distribution of sensors.

Margarida Sardo, Senior Research Fellow at UWE’s Science Communication Unit echoed this during her presentation at the SDG Conference- “Making project engagement and evaluation work across European cities and cultures”. Sardo provided tips for running large scale European citizen science initiatives, pressing the need for research to be able to span continents.

Such knowledge sharing is exactly what platforms such as EU-Citizen.Science, Citizen Cyberlab and CS Track endeavour to cultivate. By show casing projects and hosting forums discussing issues from identifying participants to modify protocols and data analysis, the sites aim to build on the growing impact of citizen participation in research.

As WeCount progresses, it too can- and must- learn from similar citizen science initiatives. Projects like EnviroCar, an App for collecting car sensor data to improve municipal traffic management, offer crucial case studies for addressing installation of technology and data privacy- details essential for any citizen science initiative.

While COVID-19 continues to interrupt research, and institutions are forced to economise in the face of funding cuts, citizen science will become increasingly critical. If the pandemic has taught us anything, it is that ‘no (wo)man is an island’. We need to develop forums for sharing best practices; without building on previous initiatives and learning from neighbouring projects, progress will be slow.